“A map of part of New-York Island showing a plan of Fort Washington, now call’d Ft. Kniphausen with the rebels lines on the south part, from which they were driven on the 16th of November 1776 by the troupes under the orders of the Earl of Percy. Survey’d the same day by order of His Lordship by C. J. Sauthier.”

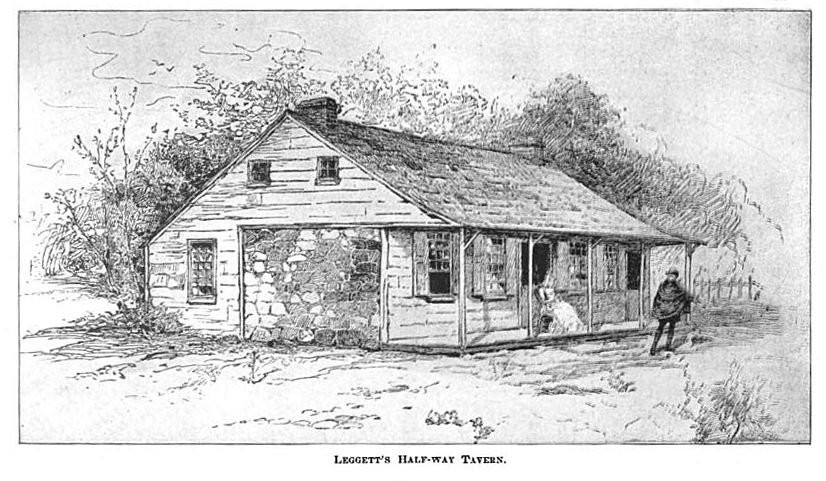

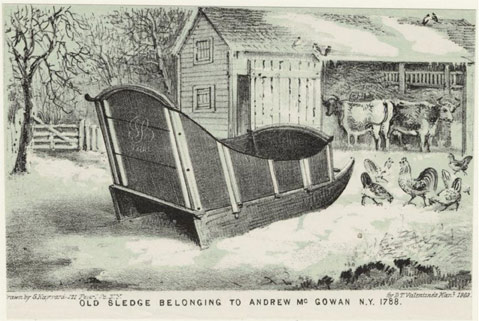

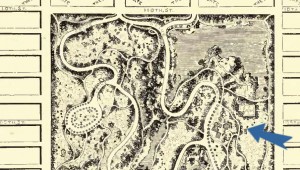

Thus the ponderous title of a Revolutionary War map that fascinated me when I first saw it a little while ago on a site devoted to the ancient watercourses of Manhattan. The site provides a nice detail of the McGowan homestead (and their adjoining tavern, the Black Horse, which is not here named, though steadily patronized in the late 1770s by British and Hessian troops),  in what is now the northeast section of Central Park. Here is the detail:

But it was a complete puzzlement for me. Take a look at that Kingsbridge Road, here the “Road from New-York.” It is shown as leading almost directly north from the McGowans’ place into Harlem, slightly to the east of some fortifications, while another unmarked path seems to fork off to the left and dead-end in another fortification (just above the letter w in “McGowan’s Pass”).

Now, from what I know of Central Park, such paths seem incomprehensible. Both sides of the fork would lead down very steep hills, unless the topography then was vastly different from what it is now. Take a jog on Central Park’s East drive around 104th St. and check out the paths leading down into the Conservatory Garden and to Fort Clinton, and you’ll see what I mean.

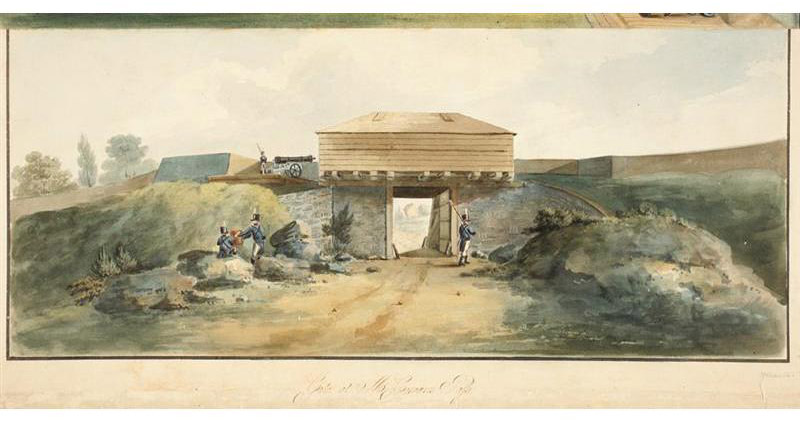

And there is no representation whatsoever of the hairpin switchback, where Central Park’s East Drive swerves hard to the left and goes almost due south for about 200 yards (around the n in “Advanc’d Postes” here) before turning around and pointing north again. According to maps and drawings from the early and mid-1800s, this switchback road was very in place during the War of 1812. And why shouldn’t it have been? It followed the natural terrain. Furthermore, the “Road from New-York,” heading north, is not even aimed in the direction of Fort Washington.

It took a long time before the obvious answer occurred to me. The map is a lie!

Military disinformation, if you will. The British would not have published an honest map showing the proper roads —not in wartime and certainly not in late 1776 or in 1777.

This was the era when the Redcoats hanged Nathan Hale as a spy over on the East Side, and elegant spy Major André was trading notes with disgruntled colonial Benedict Arnold about how best to turn West Point over to the Redcoats. No, the British knew what the route was, down the winding road from McGowan’s and over to the west, and up north another three miles to Fort Washington (or “Fort Kniphausen,” as it was renamed when General von Knyphausen of Hesse took it over). The British and Hessian armies no doubt had good maps, but they were hand-drawn, top-secret, and carried around in officers boots; not distributed as lithographs suitable for framing!

Postscript: This was one of the first posts to the blog, and I now find my conclusions and attitude very rash, particularly in the above paragraph. “It’s all lies!” is a good place to begin for any amateur historian, since you won’t find anything worth having if you don’t scratch below the surface.  But sometimes a cigar is only a cigar. The content of the map may well be biased, but probably not by much. The direction of Kingsbridge Road north of the Pass is actually consistent with what we see on later [American] maps from the 1780s and 1810s. The East Drive switchback was not platted out till about 1860, although there was certainly a trail along that approximate route.

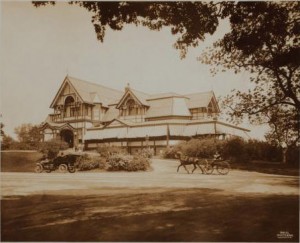

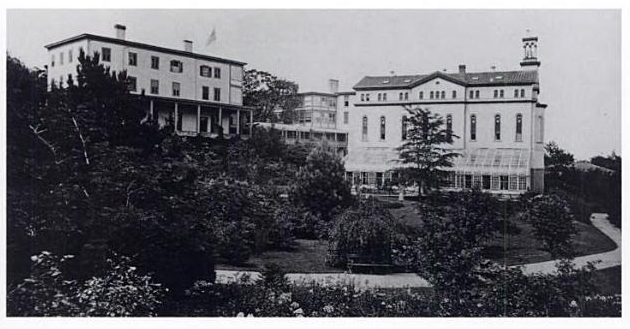

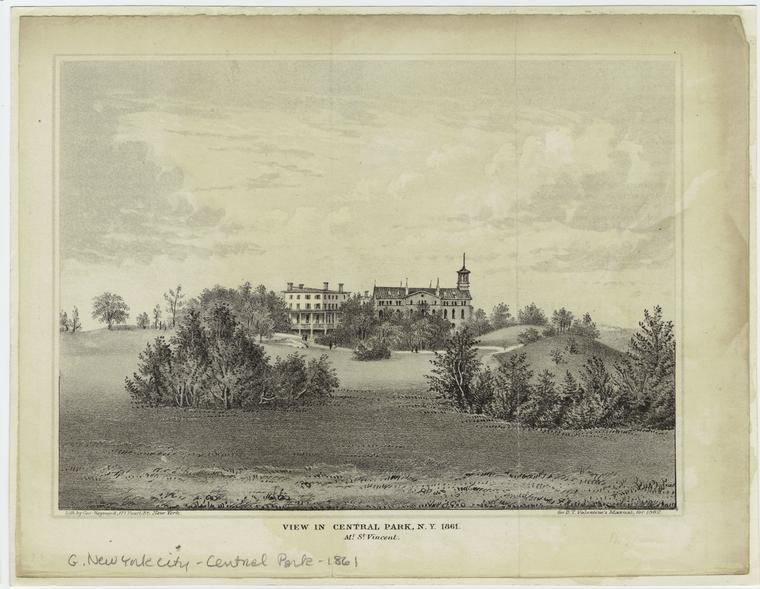

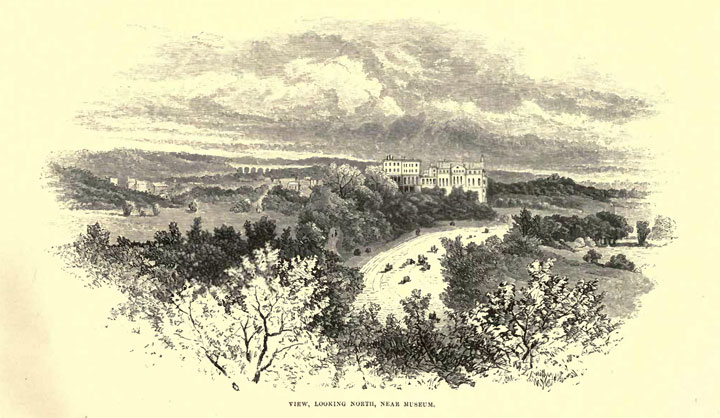

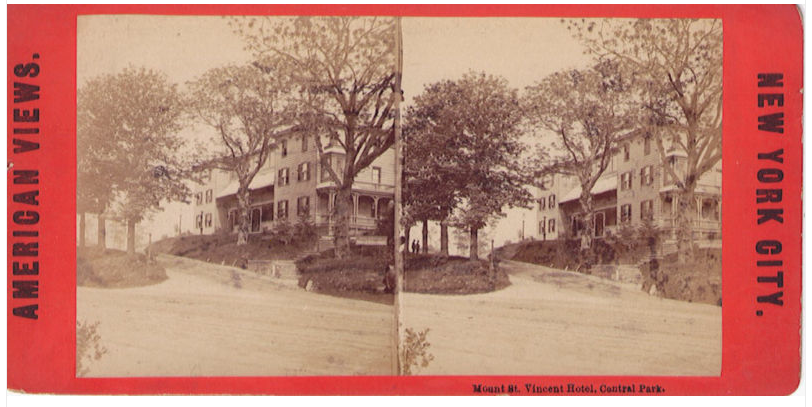

There were a number of stereoscopic views of this area manufactured in the 1860s and 70s. This is pretty much how things looked when Frederick Law Olmsted and his family lived here, 1859-1862, while Olmsted was directing the construction of Central Park.

There were a number of stereoscopic views of this area manufactured in the 1860s and 70s. This is pretty much how things looked when Frederick Law Olmsted and his family lived here, 1859-1862, while Olmsted was directing the construction of Central Park.